With Fidel Castro gone, Cuba's Catholics hope to regain ground lost to Santeria

Havana, Cuba – For many Cubans, especially the elderly, being forced to practice their Catholic faith in hiding is still a fresh, painful memory. As the country’s president and supreme leader, Fidel Castro tried to eradicate the Catholic Church from the national consciousness, discouraging younger generations from attending mass with their parents and sending priests to re-education camps. He also eradicated holidays from the calendar and prevented the faithful from holding state jobs.

“My father had to always keep our annual Christmas tree away from the windows,” one parishioner at the Church of San Francisco in Old Havana, who preferred to remain anonymous, told Fox News Latino. “My parents were determined that our traditions would not be lost.”

With Castro now gone, many here are confident of a religion comeback in the coming years.

Nuns from Havana’s Madre Isabel monastery say their congregation has more adherents than ever.

“The monastic life is very attractive to many [female] Cubans, who have suffered for years under the oppression of men, and are now looking to devote themselves to the work of God,” one told FNL.

“Seminary schools across Cuba in particular are attracting more would-be priests than ever before.”

Shortly after the Cuban Revolution in 1959, church services started being watched closely by the communist regime — so much so that police and military officials would be posted at the doors of churches to monitor sermons and record attendance.

“In the 70s, my mother would take me to churches in neighborhoods where we weren’t known in order to avoid being recognized,” the parishioner who requested anonymity told FNL. “No provisions were given for the priests, and we often had to improvise the sacramental wine, because none was available.”

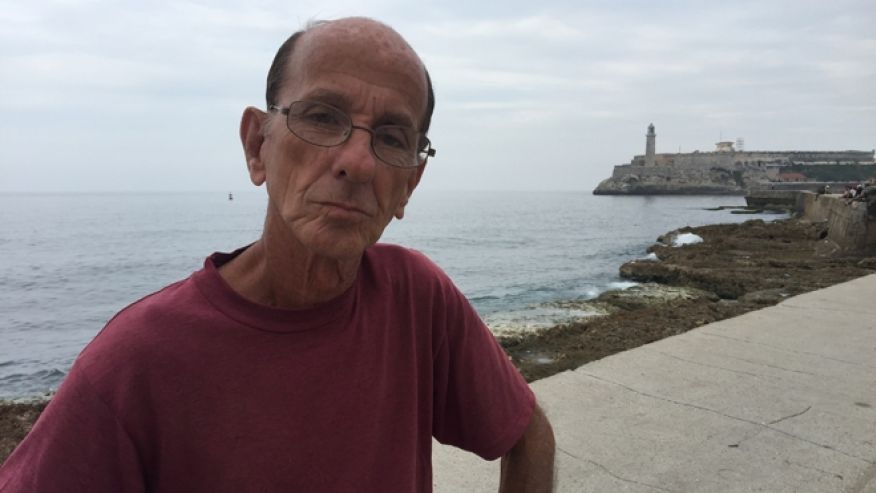

Rene Santos, now 70, also recalls the years of oppression.

He was just 13 years old when the revolution rolled into Havana, he said, and changed his life forever. His Catholic faith became a burden.

“I was told by my university that if I wanted to study medicine and become a doctor, that I would have to recant my Catholicism,” he told FNL on Havana’s famous waterfront, the Malecón. “The idea was unthinkable. I didn’t see what one had to do with the other.”

“The government didn’t care that the older people kept their faith, but they encouraged the younger generations to reject it,” he said. “Many of my friends did, but, in the face of poverty and hunger, my faith was one of the only things that kept me going.”

Castro also forced the closure of a number of Franciscan monasteries in Havana, institutions that were founded soon after the Spanish conquest in the 1500s, repurposing some of their buildings as offices for “Defense of the Revolution” neighborhood groups — which were often the ones that went around reporting to the government which residents were displaying religious symbols like Christmas trees in their homes.

Castro’s war against Catholicism created a vacuum which was partially filled by Santería, an Afro-Caribbean religion mixing elements of Catholicism and African traditions.

Once a back-room faith, Santeria now proliferates in Cuba — santeros are easy to spot in Havana, as they dress entirely in white and they often seem to outnumber members of more traditional faiths.

Their “cleansing” and “mounting” ceremonies, which frequently involve animal sacrifices, tend to attract younger Cubans who grew up in austerity.

Late in his rule, however, Castro began to ease restrictions on religious practice, much of which was concessions to the Vatican that allowed Pope John Paul II to visit the island in 1998.

A few monasteries and convents reopened their doors in the years since, including Madre Isabel and the Convent of Santa Brigida.

Castro remained a modest proponent of the Church after handing over power to his brother, Raúl in 2006, and every pope since has visited Cuba.

In 2014 the current pontiff, Pope Francis, acted as a mediator between the U.S. and Cuba to begin discussions to re-establish diplomatic ties, a move that paved the way Barack Obama’s state visit as president.

This would explain why the Cuban dictator found an unlikely set of mourners among the island’s Catholic population.

“Fidel Castro made it very difficult to be a Catholic in Cuba, but we are still sad to see him pass away,” said the parishioner at the Church of San Francisco in Old Havana.

Part of that is pride, she explained. “Those Catholics who remain in Cuba today can celebrate having remained strong in their faith despite great external pressures.”